Dive Motels, Greasy Spoons, and the Legacy of Jim

Living in a small southern Nevada town tucked into the arid desert was good for exploring and dreaming as a boy. A town too big to throw a stone across, but one you might have been able to walk end to end if you were determined.

We rode bicycles everywhere we didn’t walk, everything was so close. Friend’s houses, the park, dirt alleyways, school, always leaving them unlocked, and always finding them where we left them. Day, night, it didn’t matter. Such was the time.

My school’s open floor plan, with its sizeable area in the center, gathered students for “homeroom” each morning before moving to doorless classrooms spread out like pieces of a pie. This school room concept drew a lot of noise back in the 1970s, but one thing they were not is noiseless.

One summer evening we traveled into Las Vegas to eat dinner at The Flamingo, a long established historic casino, hotel and restaurant. A friend in the 4th grade had given me a little tip about the place that day, one I was going to verify for myself. When we got to the restaurant and the maitre d’ in his nice black suit was ready to seat us, I blurted out, “Is this place really run by the mob?!” Which, well, of course it was, but wasn’t something anyone said, ever. My father just about crapped a brick, as my mother went pale.

The maitre d’ let out a barrel laugh, “Everyone is welcome here!”

He gladly seated us. My parents gave a sheepish smile. After he was out of earshot, my father turned straight to me in a very stern, but hushed voice, “Where did you hear that?!”

“Uh, Jimmy Lindsay.”

“Do not ever, EVER say that again! Anywhere!” My mother said.

“Uh…"

“You understand me, mister?”

“Okay.” was about all I could muster.

“And I don’t want you talking to Jimmy Lindsay anymore. He’ll probably never get past the fourth grade.”

One week dad determined it would be okay if I missed a couple days of school, as this was the only chance we were likely to see his great aunt Emma in the strangely named Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. I wasn’t entirely sure what that name meant, but was glad to get out of school and go somewhere new.

We stuffed clothing into small suitcases, tossed drinks in an ice chest, piled into dad’s mustard yellow Chevelle and were off. It wasn’t more than a handful of miles past the gas station that the AM radio in the car went on the fritz, with the tuner knob no longer functioning. We listened to the last aural vestiges of the only station we could get fade away, just like the last few dwellings outside of town supplanted with more dirt.

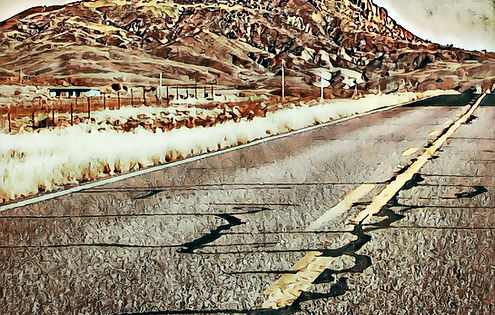

When we hit Arizona, the radio long gone, miles of open road were upon us. The American West. Dirt and rock hills, scrub brush, tumbleweeds dancing from one end of nowhere to another.

With the sun setting behind us, we found a no-name inn, little more than a white sign with the word “Motel” written on it.

Barely more than a dozen rooms, it looked like half were out of commission. Twenty-two bucks was the going rate, a bald man curtly informed my father. Dad took out his wallet and handed him some bills. The man handed him a key with an elongated diamond key chain and we made it to our room.

As we pulled things from the car, dad dug through his old Levis, finding a dime that would fit in the pay phone outside at the end of the rooms, near the lobby. He wanted to give Emma a call, letting her know we would be there tomorrow afternoon. Did aunt Emma worry that much? I don’t know.

Inside the room, we turned on the old tube TV with only three channels.

“Change it to 3,” mom said to me as I stood in front of it, turning the dial.

The news came on, and an unfamiliar man spoke about an unfamiliar town, but not the one we were staying in, as it was too small.

After the sunset and we shut the TV, then the light off, I marveled at the glow that still came from the TV screen, acting like a nightlight that slowly faded.

There was noise from next door, not just people talking, but movement, springs on the bed like someone was jumping on it. I know my dad hated it when I did that. It soon abated, and I assumed some parents scolded their kid, who stopped. My dad however, speculated the couple there had, “moved their operation to the floor.” A concept that escaped me for years.

Time passed, but I couldn’t sleep, rustling about. Mom either, and noticed. “Come on,” she said.

We grabbed something to put over our top, a sweatshirt of some sort, stepped outside.

“Look up.” She said. I did, where a billion stars greeted our eyes in the moonless desert sky.

Back inside, the rare car passing by on the highway subsided into silence, until fragmented sounds of a distant freight train, carried by gusts of wind, brought peace to my mind and I drifted off.

After mom and dad drank coffee from the lobby and offered me milk I didn’t want, dad agreed to drop a quarter in the soda machine in the lobby with its fading front panel. He opened its little side door, telling me to pull the one I want.

I reached for one with the Coke bottle cap logo facing me, but wasn’t strong enough. “I can’t.”

He helped, and with one tug, the bottle released, replaced by another. He used the opener on the side of the machine to get the cap off, as if he had done it a thousand times before, because he likely had, and handed it to me. Mist spilled out of the top. The glass bottle was so cold I could barely handle it.

While my parents fiddled with their coffee, I rummaged through pamphlets tucked in a display. Petrified forests, ghost towns, and a secret map showing where the Superstition Mountains held tales of lost Dutchmen looking for gold never to be found.

“Look!” I said, sharing my curiosity.

“Put that tourist trap stuff back,” my father barked at me, deflating my excitement.

We wandered into a small dive of a breakfast diner. It may have been the only one in town. It was a scorching morning, and the sun, despite being in the opposite direction, seemed to pour in its light through the large front windows, music playing from a small radio plugged into a shelf high above the counter. The establishment was narrow, faded paint that was once probably white, with a row of peeling red leather counter seats near the front, where we sat. Scattered, old, chipping linoleum tables with chrome painted legs dotted the back of the room.

Mom gave a humbling grin, uttering something about the “greasy spoon” we were in.

I asked her why she called it that? Greasy spoon, what a strange name, and she explained how the term came to be, “In these cheapest of the cheap places they may never wash the dishes, instead merely wipe the spoons ‘clean’ leaving a small layer of grease behind.”

It took me a moment to gather that icky thought in, if it really could be true, as she went about her business looking at the menu. My dad festered just a little at her blunt comment, happy to just be able to eat a hot meal, greasy spoons or not.

The music on the radio stopped when a news man cut in. We all grew a little quiet when the matter-of-fact voice crackled through about a special report. “In some tragic news, singer Jim Croce and three companions were killed late last night in a Louisiana plane crash. Croce was 30. We now return you to your regularly scheduled programming.”

It took a minute for me to comprehend the gravity of what I had heard. One of the first moments of loss, genuine sadness, I remember feeling in my life, which had been so happy up to that point. Thirty was younger than parents. People didn’t die at that age, did they? Croce with his storytelling and open smile was a favorite of my dad’s, mine too. Shocked, dispirited, I so wanted it to not be true. My dad was flat, sullen, as my mom tried to explain it away as gently as she could. “These things happen, honey. They are really rare, but they do.” Her words tapering off, trying to assure me somehow over time I would be okay.

We drove the rest of the day, not much said between us, staring out the car windows, staring down the scenery while the miles just rolled away. Countless white lines on the black top disappearing beneath the car as the warm sun inched its way across the blue behind us. It was almost like being home; the moments where nothing much happens and you just think. As a boy, life usually felt like I had all the time in the world to see anything I wanted, with Jim Croce taken from us so coldly, so abruptly like that, I was able, even in my developing mind, to reflect.

After a while, I think mom just couldn’t sit anymore. She opened and folded the map back and forth, trying to get the right section of road we were on to face out, staring at it for a while, making sure we were going the right way, which we were.

We passed a few small towns, breaking up the monotony of the endless road, visibly reconnecting me back to where we actually were. Though we stopped at not a single one. After passing a few, they look the same, with names you’ll never remember.

It wasn’t until years later I realized it’s only when you stop, you really stop, get out, walk in new businesses, talk to new faces that make it all worthwhile, build fresh memories. Memories that may blur and fade, but contain fragments that can last decades, a lifetime.

I didn’t grasp that then, and this hadn’t been the trip for that, nor the time. The lingering thought of Jim Croce’s death hardly receded into the back into my mind, with nothing to replace that thought.

We got to Emma’s before the sun hit the horizon. A small yellow house on a dirt street with a chain-link fence guarding scrub brush, rocks, and dry weeds in her front. A grayish hardwood tree off to one side inched its way into and through power and phone lines above. Dad was glad to see her, and it was nice to see him smile again. Emma didn’t seem as old as I expected, greeting me with a smile. In the hours that followed, Jim Croce’s death never came up. I don’t even know if Emma knew who he was.

Four long decades later, when my father passed, the funeral home director casually, gently, mentioned he could play music in my father’s last physical moments on this earth before his cremation. I thought for a moment while he patiently waited, finally asking if he could play Jim Croce’s I Got a Name. He paused briefly, nodding with a little smile.